Trump’s most credible messengers are being accurate. But they’re not being honest.

If it’s possible to work for Donald Trump and still remain an honest person, we haven’t seen evidence of it yet.

Time and again, even the most serious and respected people in the Trump administration — people who were looked to as good influences on the ignorant and impulsive president, or, in a worst-case scenario, as canaries in the coal mine — have ended up going out to defend Trump over something indefensible. They may not be technically lying, but they are advancing Trump’s narrative instead of advancing the truth. And more often than not, Trump has repaid them by making them look like fools — admitting he committed whatever sin they’ve helped to cover up.

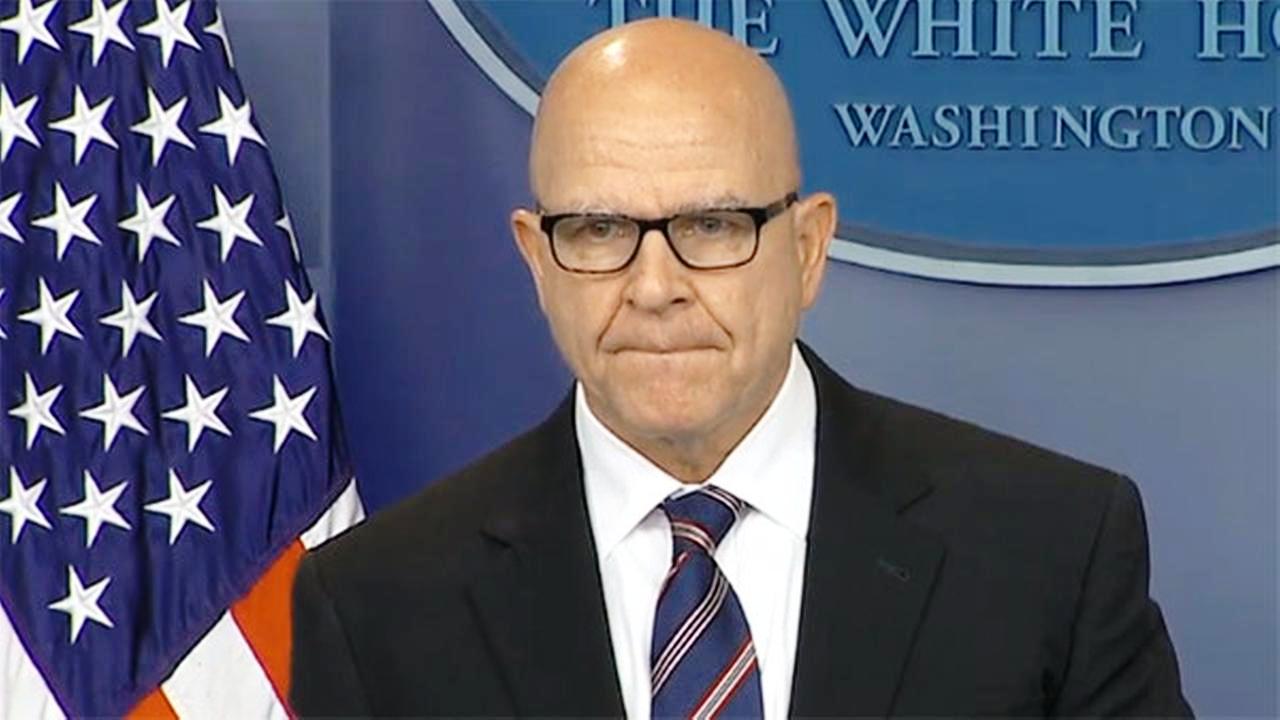

National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster

Take National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, who was trotted out to the press Monday night to push back against reports that Trump had divulged super-classified information to the Russian foreign minister and ambassador during a meeting last week (and possibly put a key anti-ISIS source in danger by doing so).

McMaster’s carefully worded non-denial denial all but went up in smoke by Tuesday morning, when Trump tweeted that he’d had very good reasons to give information to the Russians. By the time McMaster delivered a second press briefing Tuesday, he was affirmatively defending Trump’s decision to share information as “wholly appropriate” — and chiding the press for the “leaks” he’d earlier tried to discredit.

Something similar played out last week when Trump fired FBI Director James Comey. That time it was Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein — whose memo to Attorney General Jeff Sessions was originally presented as the reason for firing Comey — and Vice President Mike Pence, who spent a lot of time last Wednesday pointing to Rosenstein’s “recommendation” when asked about the firing. By Thursday, Trump had told NBC’s Lester Holt that he’d already decided to fire Comey no matter what Rosenstein’s memo said.

The White House communications staff (including Sean Spicer and Sarah Huckabee Sanders) routinely lies in service of the president. They say things that they either know to be untrue or have no knowledge of whatsoever and present as truth anyway (only to be proven wrong).

What McMaster, Pence, and Rosenstein have done is different. They’ve made statements that are carefully crafted to avoid saying anything that’s technically inaccurate. But those statements have been made to serve a White House narrative that is, itself, a lie.

They’re being accurate. But they’re not being honest.

McMaster didn’t technically deny the story, but his statement was designed to seem like a denial

On Monday night, when the Washington Post reported that President Trump had told Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Ambassador Sergey Kislyak “code-name sensitive” information about a source on ISIS — that is, information that is not just classified but held so closely that only people authorized to know about a particular effort can access it — Deputy National Secretary Adviser Dina Powell issued a flat denial: “This story is false.”

McMaster didn’t.

Unlike Sean Spicer (left), H.R. McMaster has carefully avoided saying anything provably false.

The national security adviser said to press that the story “as reported” by the Post was false. He didn’t point to any specific inaccuracies in the Post’s reporting. Instead, he denied that the president divulged any “sources and methods” of intelligence or any information about covert military operations — things no one was claiming Trump had divulged, to begin with. In a response to a follow-up question on Tuesday at the press briefing, he clarified — if you can call it a clarification — that “the premise of the article is false.”

Many reporters were quick to read between the lines: McMaster wasn’t saying that Trump had not divulged classified information to the Russians. Therefore, McMaster had just helped confirm that Trump had done just that.

But while that implication was certainly present in McMaster’s remarks, if you were trying to read them critically, it wasn’t the point of the statement. McMaster didn’t acknowledge that Trump had, in fact, divulged information — even, as he eventually did Tuesday, as a way to justify the president’s decision. (By that point, Trump had already tweeted that he’d told the Russians something about “threats.”)

The news outlets that were eager to accept the White House’s own explanation for what had happened didn’t come away from McMaster’s Monday statement thinking he’d just confirmed the Post’s reporting. Instead, they seized on the quote, “It didn’t happen.” They understood McMaster’s statement as a denial of the Post’s story — which is, if you stepped away from close and critical parsings of the language and took it at face value, what it was.

Reince Priebus, Mike Pence, Steve Bannon, Sean Spicer and Michael Flynn listen as President Trump speaks by phone with Vladimir Putin in the Oval Office

So when Trump himself tweeted Tuesday morning that he’d told the Russians about “threats” for “humanitarian reasons,” he didn’t contradict McMaster, just as McMaster hadn’t contradicted the Post. But Trump still undermined McMaster’s Monday statement. Because McMaster’s statement was designed to seem like a discrediting of the Post’s story, and Trump’s tweets certainly appeared to re-credit it.

During his Tuesday press briefing, McMaster split the difference. He acknowledged, and defended, the president’s decision to share sensitive information. But he insisted that the “premise” of the Post’s story was false, because the story had implied that the source of the intelligence would be in danger because of what Trump had said — “in no way,” McMaster said Tuesday, “was anybody put at risk.”

The second statement simply proved that the people who’d taken his first statement at face value — who ran with “It didn’t happen” as the headline — were the fools. The people who listened to him critically and skeptically, for the possible truths he was omitting, were the ones who’d heard him correctly.

The people playing these word games are the people with the most integrity to lose

When Vice President Pence huddled with reporters last week to defend the firing of James Comey, he didn’t even get the benefit of such a skeptical audience. Pence’s remarks focused on the “recommendation” written by Deputy AG Rosenstein, which accused Comey of undermining the FBI’s integrity through his treatment of the 2016 investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server.

As a result, Pence was widely reported as saying that President Trump had acted “based on” Rosenstein’s recommendation — or even that Rosenstein had written the recommendation without Trump’s knowledge, and Trump simply decided to fire Comey after reading the memo that came to his desk.

But Pence never actually said those things. Press secretary Sean Spicer had said them Tuesday night. But Pence simply talked a lot about Rosenstein’s recommendation, and about his integrity, and let the reporters fill in the blanks.

So when Trump said the next day that the recommendation was irrelevant, it was possible to point to things Spicer or Sarah Huckabee Sanders had said that had just been proven to be lies. But it wasn’t possible to point to anything Mike Pence had said that was false. Reporters had just understood the function of what he was saying, rather than taking a gimlet-eyed look at the words he wasn’t using. They hadn’t distrusted him enough.

Vice – President Mike Pence speaks with reporters following a GOP caucus meeting at the U.S. Capitol

Rosenstein hasn’t talked to the public about his memo. But the memo itself contained an act of careful wording: Despite the implication of Pence and others in the administration, Rosenstein never technically called on Comey to be fired. He simply wrote a memo that was presented as justification to fire him — to cover up a predetermined decision made by the president (based in part on the fact that Comey was investigating Trump).

The reason Rosenstein’s memo mattered wasn’t just because it was a written argument against Comey’s leadership — it mattered because Rosenstein was one of the most widely respected Trump appointees among the legal and law enforcement communities. When Trump nominated Rosenstein, people who’d worried that the Trump administration wouldn’t care enough about the rule of law were reassured.

That’s why Pence — whose very selection to the vice presidency was designed to reassure conservatives that the Trump White House would care about conservative values — was a key validator for Trump the next day. And it’s why McMaster — who was so widely respected among national security experts that his hiring almost assuaged the alarm that his predecessor Mike Flynn had provoked — was sent out Monday to respond to the Washington Post.

Their gravitas, in all three cases, was being used. It was used to offer excuses for bad behavior on the part of the president. It was used to bolster White House lies.

Kellyanne Conway sitting on couch in the oval office

There’s more to integrity than not saying anything provably false

The reassurance that experts and professionals felt when McMaster and Rosenstein were nominated to the Trump administration, and that conservatives felt when Pence was picked for the ticket, was twofold.

At best, their presence in the Trump administration would guide the president toward wisdom, prudence, and conscience in policymaking — it would make things better than they would be if Trump were surrounded by yes men.

At worst — if Trump really was as impulsive and tyrannical as some feared — they wouldn’t stand for it; they’d leave, and by leaving they’d show that this president was so bad they couldn’t stay.

That assumes these men are holding themselves to a high standard of integrity — that they would not allow themselves to witness or participate in anything they deemed immoral, or allow such things to go on around them.

There are other definitions of integrity. You can decide that you’re acting with integrity if you failed to stop something bad from happening but didn’t do anything to facilitate it. You can decide you’re acting with integrity if lies are going on around you but you don’t say anything that is a lie yourself.

If you’re concerned with preserving your own reputation, that may well make sense. “Yes, I was part of the Trump administration,” you can imagine someone saying a decade from now, “but they never made me lie.” You might be impressed by that. It’s an impressive feat.

Right now that’s the standard that McMaster, Rosenstein, and Pence have met. They have never made false statements. They have only been used to make falsehoods appear true — and made people look like fools for taking them at their word.

– Dara Lind I Vox I Michael Onas- Editor